Howard Gardner © 2024

You may find that question provocative! If so, please read on.

For decades, I was quite friendly with Carleton Gajdusek. On almost any definition, he was brilliant. In addition to having received the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 1976, he spoke numerous languages, was an expert on several cultures in the South Pacific, and was as well-read as any professor in the arts and humanities. In fact, with his approval, I was writing his authorized biography when something happened that caused me to stop…forever.

I’ll get to that definitive disruption near the end of this blog.

Marilyn Monroe

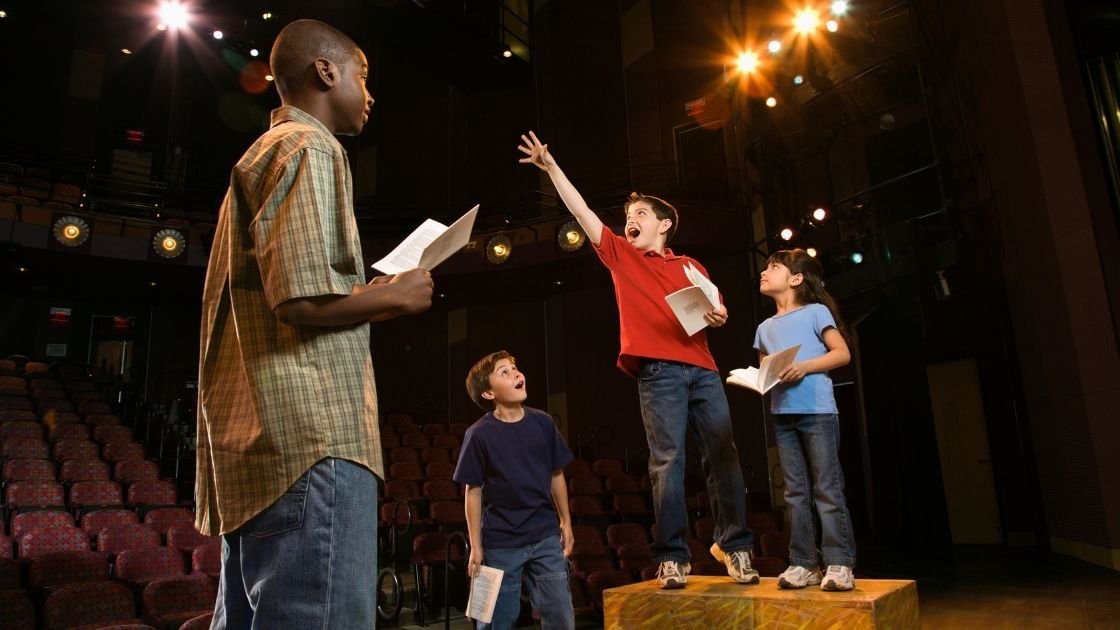

Once, in conversation, Carleton said to me: “Don’t think for a minute that actors are stupid, they are actually very smart. Marilyn Monroe would not have gotten as far as she did, in the way that she did, if she hadn’t been very smart.”

I probably would not have remembered that comment, except that recently I’ve been involved in discussions with psychometricians who have a quite specific definition of what it means to be smart. In a phrase, it means that you do well on an IQ test—or one of its equivalents, like the SAT from the Educational Testing Service. And if you don’t score well, then you can’t be smart, at least according to what psychometricians call “high intelligence.”

As most readers will know, decades ago, I put forth a different view of intelligence—a pluralistic view called “the theory of multiple intelligences.” And once you have embraced that concept, it’s possible to return to my question in a more thoughtful way.

Dr. Thalia Goldstein, PhD

Chatting with my wife Ellen Winner, I was reminded of the quite original research carried out by Dr. Thalia Goldstein, at one time Ellen’s doctoral student. (Thalia is now a professor at George Mason University). For her first empirical study, Thalia conducted substantive interviews with eleven actors who had achieved some success in their profession. As a comparison group, she conducted similar interviews with an equal cohort of eleven well-established lawyers.

Not surprisingly, the lawyers fit the stereotype of intelligence as it is seen and measured by many psychologists. That is, the lawyers presumptively have a high IQ—they would perform well on IQ tests and other academic measures like the SAT or the Bar Exams.

In my terminology, lawyers typically exhibit linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences. In fact, I sometimes quip that a law professor is the prototype of a high-IQ person, because they are often good with language and can think logically. In contrast, a humanities professor necessarily excels with sensitivity to language; a math professor necessarily is an expert in logical-mathematical thinking—but the respective complementary intelligences are optional, or at least not vital. Indeed, individuals displaying the most extreme examples of linguistic intelligence, or of logical-mathematical intelligence, rarely stand out with respect to the other intelligences.

So, what about actors? According to Thalia Goldstein’s and Ellen Winner’s analysis, what stands out in the case of actors is their personal history. From an early age, future performers observed other people carefully and often sought to imitate them faithfully. These future actors often felt alienated from their family and its surrounds and aspired to lead a different kind of life—often imagining it and trying to enact, readily envisioning alternative (fictional) worlds. Typically, the actors did not like school, where they were expected to follow the norms of the classroom, do the work that was assigned, and not to dream or act out. Put more generally, they sought a different kind of existence and found the stage or the screen a place where—despite typical discouragement from their parents—they could enact different personae, ones unlike their own.

The research confirmed: In all of these respects, the eleven actors differed from the eleven lawyers.

Donning the lens of “MI theory,” what else might one say?

Naturally, if a young person wants eventually to become an actor on the theatrical stage, she or he has to have a good memory for lines—this facility with language is less important in television or movies, where one need not memorize large amounts of text. Still, a person with poor linguistic memory would unlikely be attracted to performance—unless as a mime or as an actor (say, Buster Keaton) at a time when “pictures” were silent. As for logical-mathematical intelligence, that’s fine—but it is an option, rather than a requirement, unless a budding actor should want to be one’s own agent or start one’s own production country or play the stock market successfully.

As for the other intelligences: Depending on what kind of actor a young person aspires to, one would need musical intelligence (to be involved in musicals or the opera), bodily-kinesthetic intelligence with the desired stances, moves, gestures—both of the body as a whole and of particular limbs—and spatial intelligence (if one’s stance vis-à-vis the audience, the other performers, the camera, etc. is critical).

Just as performers need to draw on various intelligences, different performing venues also foreground different configurations of intelligences.

We can look at these configurations in another way: By the age of 10 or 12—and sometimes much earlier—one should be able to predict who is likely to become a performer, and who is likely to become a lawyer. The latter young persons typically like schools, do well in academic matters, and do not have much of a fantasy life—though presumably some of them like to argue!

Getting back to Carleton Gajdusek’s admonition. He would not have been correct if he had claimed that actors need to have the same intellectual profile as lawyers. But if—borrowing the language of multiple intelligences—Carleton had spoken about a combination of linguistic intelligence and personal intelligences, with the option of musical or bodily-kinesthetic or spatial intelligence, he would have been on the mar!

Alas, despite Carleton’s lavish cognitive gifts, he unfortunately behaved abhorrently. He adopted many youngsters—almost all boys—from islands in the South seas and raised them in suburban Virginia. He abused some of them, was arrested and convicted of pedophilia, and after several months in an American jail, spent his last years essentially in exile in Norway.

And of course, Marilyn Monroe came to an equally unhappy fate—at the age of 36, she overdosed on barbiturates.

Whatever form of brilliance you may have, it’s no guarantee that you will lead a long or a happy life. And indeed, the fate of so many television and movie performers—more so women than men, I believe—confirms that depressing ending. Even an abundance of intelligences is no guarantor of a well-lived life—what I would term a “life of good work.”

A more general takeaway

As readers of this blog know, many psychologists and psychometricians believe that the IQ test (with its general factor) can predict success across the vocational landscape (see an example of this I recently blogged about, linked here.) To be sure, no one would readily decline the gifts of linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences. But to simply conclude that actors are smart, or that actors are dull is simplistic. One needs instead to ask what kind of an actor and what configuration of intellectual strengths.

Reference

Goldstein, T. R., & Winner, E. (2009). Living in alternative and inner worlds: Early signs of acting talent. Creativity Research Journal, 21(1), 117–124.