Notes by Howard Gardner

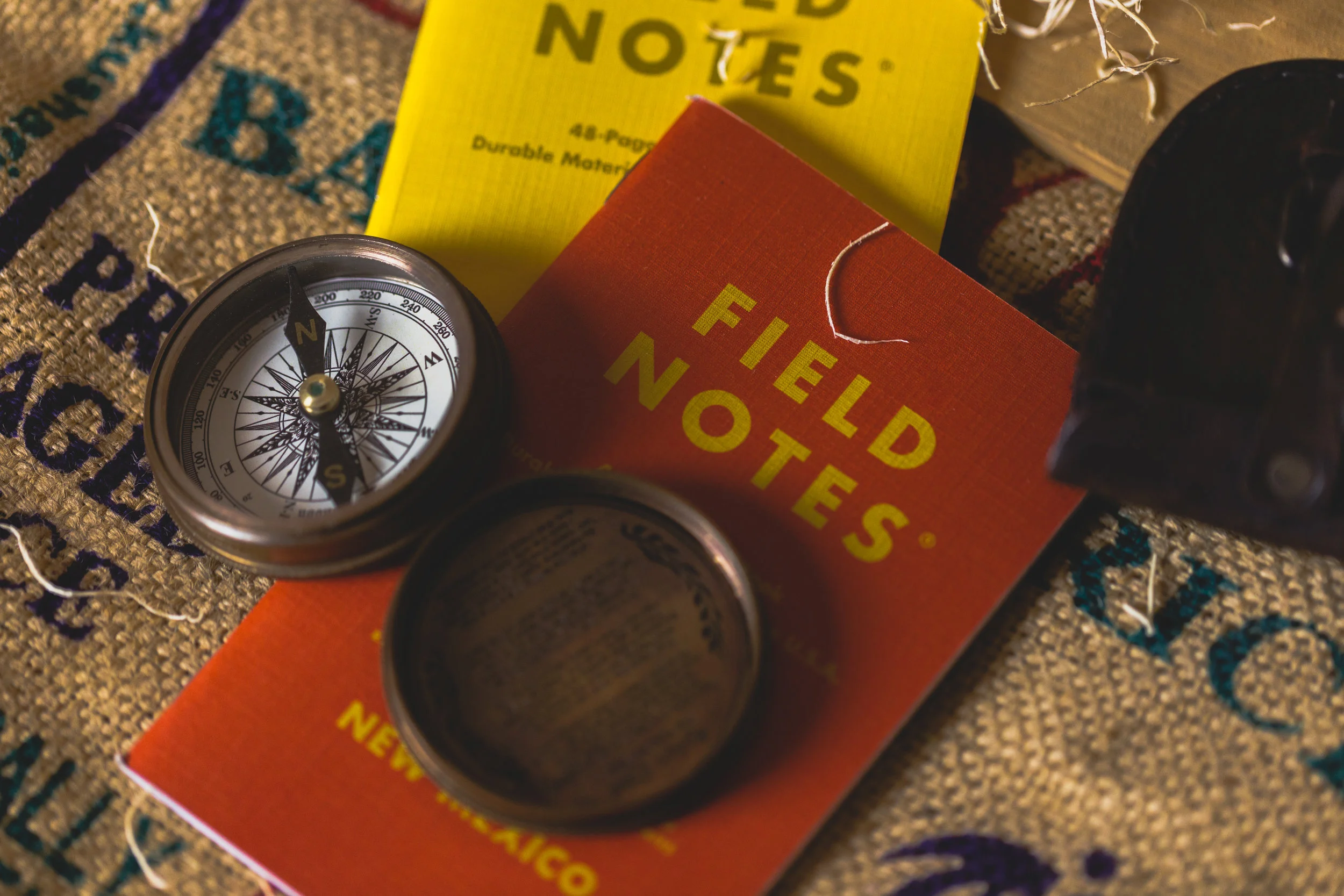

John Edward Huth's book The Lost Art of Finding Our Way, featured in an article from The Chronicle of Higher Education, is a text that collects the various methods of navigation used by our forebears that have been dwindling due to the rise of technology.

When I developed the theory of multiple intelligences more than thirty years ago, I keenly remember one of the chief stimuli for the theory: my fascination with the capacity of navigators in the South Seas to find their way among hundreds or even thousands of islands, covering hundreds of miles, without a compass or any other technology. As I put it, they were able to use their ‘spatial intelligence’ to navigate, attending to and synthesizing such features as the configuration of stars in the sky, the feel of the vessel as it passed over the waters, and occasional landmarks. At the time I thought, "Human beings have a remarkable range of capacities; but how they are developed and nurtured, and to what end, is determined by the needs and desires of the ambient culture."

Three decades later, on an entirely different research trek, Katie Davis and I tried to understand in which ways young people today differed from their predecessors (including my peers and me over half a century ago). Of course, nearly all sources of evidence underscored the importance of life in a digital world. Ultimately, we determined that what defines this generation most sharply is their immersion in the world of apps. Not only are they always on the lookout for the app that will allow them to execute a task quickly, efficiently, and neatly; but to some extent, they see their whole life as a series of apps, what we wryly termed a "Super App."

Nowadays, almost all of us are beneficiaries of the app world. And few of us would throw away a GPS that would allow us to get from point A to point B efficiently.

But what happens if the technology breaks down? Or what happens if we are so app-immersed that, once at point B, we simply activate the next app for the next episode of life?

To address this dilemma, Katie and I introduced a distinction between app-dependence and app-enablement. An individual is app-dependent if stymied should the relevant app, for any reasons, not be readily available. A person is app-enabled if she uses the app when it is available, lets the app free her up for other activities, and, in the absence of the app, is still able to pursue her goals.

From my perspective, one educational implication is clear. It is great if young persons are able to use compasses, more complex navigational systems, or GPS; but this technological enhancement should not be achieved at the expense of developing our brain-given cognitive capacities. And that means, we should all have the experience of finding our way around, in the absence of any external devices; and we should learn that, if one gets lost, one inevitably will find one’s way back home.

To read the article in its entirety, click here.